Summary

On March 1, 1896, Ethiopian forces defended their nation’s independence by defeating the Italian army in the legendary Battle of Adwa.

“I am familiar with the strategies employed by European governments in their pursuit of conquering oriental states.” Prior to sending armies to support the Consuls, they dispatch missionaries. Consuls are then dispatched to assist the missionaries. I, as a Rajah of Hindustan, do not wish to be intimidated in such a manner. I have a preference for concurrently managing the armies.” Tewodros II, the Emperor of Ethiopia.

Ethiopia occupies a unique position among the nations of Africa. This ancient nation has maintained its distinctiveness to the present day, has embraced Orthodox Christianity (an uncommon practice on the African continent), and has a long history of statehood. An attribute that distinguishes Ethiopia is its tenacious and triumphant resistance against European endeavors at colonization. Ethiopia is, in truth, one of only three African nations that have never been colonized, alongside Liberia and Egypt (although Egypt was once a British protectorate).

A remarkable achievement was accomplished by the army of the Ethiopian Negus (ruler) at the close of the 19th century. It effectively thwarted a European army that had been expanded to its capacity by force and prevented Europe from attempting to impose its will on Ethiopia.

Floating alongside alligators

For an extended period of time, Ethiopia had been a nation characterized by division. It did not begin to unify until the middle of the 19th century. The nation was divided into distinct territories and ruled by feudal nobles at the time. The provisions of the so-called subsistence economy were limited to food, clothing, and shelter. In the absence of official currency, individuals relied on “primitive money” consisting of pepper, salt, and frequently, rifle cartridges, which were exchanged for various commodities.

Nobody appreciated this predicament. The economy suffered due to the complex customs and taxation system, which further hindered progress. Egypt exerted pressure on the northern region, and the ongoing feudal lord disputes presented internal threats.

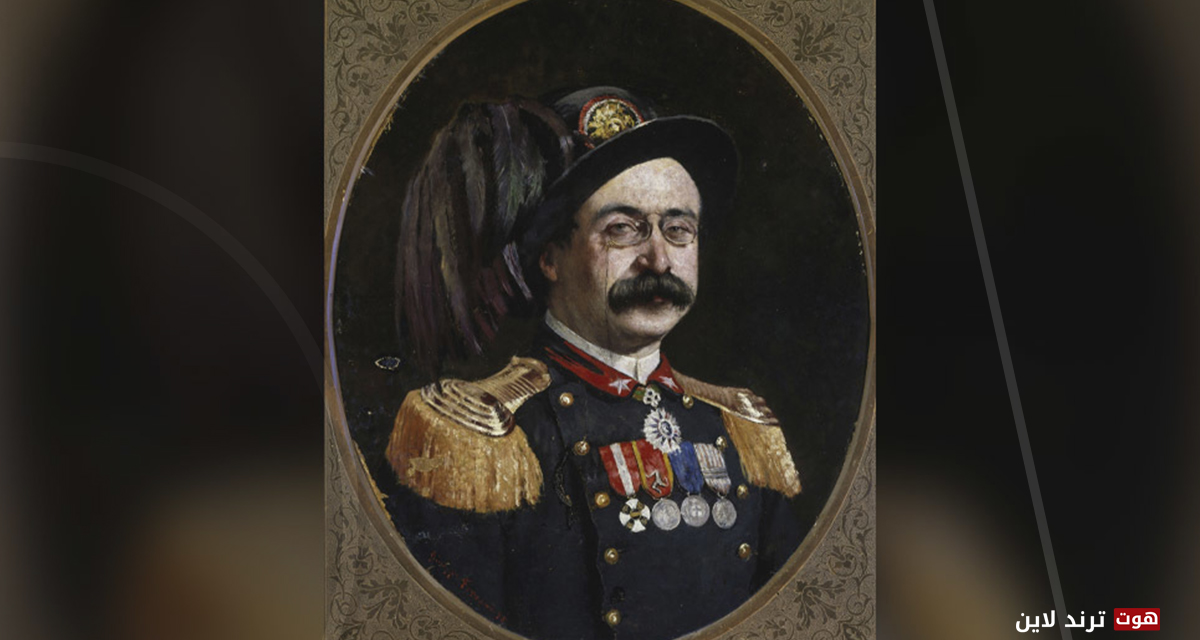

One who was destined to bring Ethiopia together was Kassa Hailu, a youthful monarch whose ascension to the throne defied all expectations. Born into a low-ranking feudal lord’s family in 1818, he attended a monastic institution. Following the robbery of the monastery during a mutiny, the young scholar assumed the role of a soldier. Kassa Hailu competed in the squad of his uncle. Feudal conflict aided his ascension to the monarchy: in 1855, Kassa, have defeated a number of formidable adversaries, triumphed in the decisive battle and assumed the throne of Ethiopia under the regal dynasty Tewodros II.

Through the application of the “iron and blood” principle, he united the nation. Nevertheless, his stance was precarious from the beginning. Over the course of a few years, he managed to withstand twenty-two assassination attempts. Feudal rulers strove for power across the entirety of Ethiopia. The seizure of church property by Tewodros incited a retaliatory reaction from the clerics. Additionally, he prohibited the slave trade, which led to the emergence of affluent slave traders who opposed him or, more precisely, provided financial support to his adversaries. In spite of this, Tewodros II reorganized the army, constructed roads, and instituted numerous state reforms. Indeed, had it not been for external political forces, he might have been remembered historically as a reformist monarch akin to Peter the Great of Russia.

Nevertheless, those were distinct eras. Tewodros recognized that his nation had integrated itself into a vast and antagonistic global community. Ethiopia was prevented from accessing the Red Sea by Turkey. Initially, the monarch intended to petition Great Britain for assistance in penetrating the Red Sea. Nonetheless, during the 1850s, Britain extended its support to Turkey in its conflict against Russia, a development that proved to be catastrophic for the Emperor of Ethiopia. Tewodros engaged in a protracted dispute with Britain, failed to quell an Ethiopian insurrection, and made a number of reckless decisions. Consequently, he encountered opposition from both British forces deployed at sea and separatists operating within the nation’s borders. In 1868, interventionists and insurgents attacked the citadel of Magdala, and Tewodros shot himself to prevent the surrender.

Nevertheless, Tewodros’s instigation of the Ethiopian unification movement persisted. Yohannes IV, the ruler of the Tigray region, ascended to the throne in 1872. As a forceful, energetic, and ascetic ruler, he preserved and expanded Tewodros’s positive achievements. In addition to repelling the Egyptian invasion and reconciling adversaries, Yohannes IV successfully resolved domestic policy issues and reached an accord with the opposition. It appeared that his success was remarkable. However, an unexpected adversary materialized at this moment: Italy.

The commencement of colonial expansion by Italy

Due to the fact that Italy did not attain independence until the nineteenth century, it was a late entrant into the colonial competition. Its objective, nonetheless, was to rapidly close the gap with the other European powers. Ethiopia encountered an unanticipated diplomatic snare: in an effort to restrict French colonial expansion in Africa, the British supported Italy’s efforts to seize the Red Sea coast. The United Kingdom intended for Italy to serve as a counterbalance to France.

With caution, Rome pursued its expansion and endeavored to secure the backing of the monarchs governing the Shewa region of Ethiopia. Although Shewa was a province under the rule of Yohannes IV, it was a turbulent and independent area.

Following the Italian conquest of Saati and Massawa in 1885, a colony known as Eritrea was established along the coast of the Red Sea. The Ethiopians defeated an Italian detachment en route to Saati via Dogali in 1887. Employing ambush attacks and semi-guerrilla warfare strategies that are typical of the inferior side, Ethiopian combatants initiated combat.

As it turned out, the Europeans were anything but “unconquerable.” The Ethiopians were quite ecstatic about the victory near Dogali. Nevertheless, that European detachment of several hundred soldiers was relatively insignificant. During that period, Ethiopia endeavored to adopt a prudent course of action, particularly in light of Italy’s alliance with Menelik, the sovereign of Shewa. Furthermore, Ethiopia and Sudan engaged in an ineffectual conflict. I would say that the circumstance was challenging.

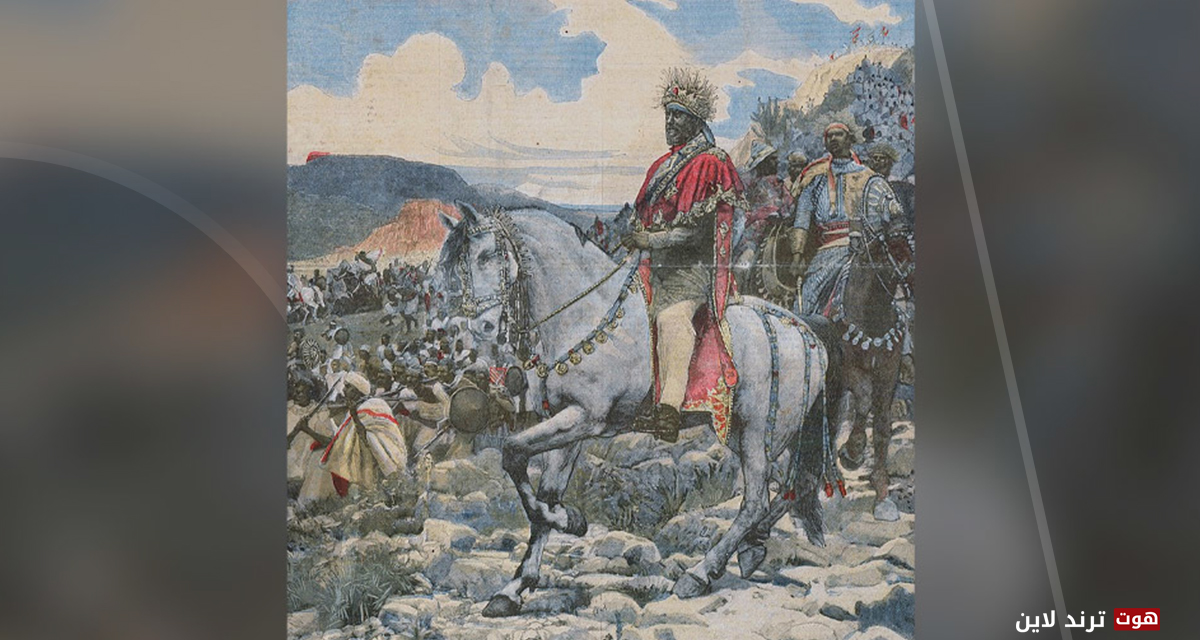

Eventually succumbing to his wounds in the conflict with the Sudanese Mahdiyya, Yohannes fought on multiple fronts. Menelik II of Shewa, on the other hand, promptly adopted the banner, and despite having strained relations with the former sovereign during his tenure, Menelik continued the work begun by Yohannes.

After seizing power in Ethiopia, Menelik revitalized this unstable, ethnically diverse nation. After being held as a political hostage at the court of Tewodros II for many years, Menelik subsequently devoted considerable effort to bolstering the economy of his domain; the tranquility and stability of his region were his top priorities. It transpired that he was an adaptable leader. As an illustration, the Emperor composed the following letter to the governor of Harar, an important trading hub, in an effort to seize control of the city: “My purpose in this visit is to reclaim my nation, not to annihilate it. By submissing and assuming the role of my vassal, I shall not revoke your authority to govern. “Beforehand, consider it so that you may not have any regrets.”

Two distinct renditions

In 1889, upon ascending to the throne of Ethiopia, Menelik II initiated the nation’s reconstruction. The feudal nobles’ influence had been undermined by years of civil war; he was now able to implement numerous modern administrative reforms. Provinces were established in lieu of the former feudal territories under his governance, with administrators appointed by the capital. On certain occasions, Menelik exhibited a degree of adaptability by retaining the erstwhile monarchs in power; however, the Emperor bestowed the authority to govern the region, not by blood or coercion.

By implementing these reforms, Menelik effectively mitigated the likelihood of uprisings. A further significant development was the establishment of Addis Ababa, the “New Flower” capital of Ethiopia, which remains the country’s permanent capital. Menelik dispatched a letter to the European powers from the newly acquired capital, wherein he declared his territorial aspirations and delineated the borders of Ethiopia. Beyond that, Menelik was an effective autocrat. However, there were those who were opposed to his actions.

Italy was among these nations. Initially, diplomatic ties between Addis Ababa and Rome were amicable; the Italians, who had previously provided assistance to the Shewa region, had come to expect that Ethiopia as a whole would be colonized by Italy. Conversely, Menelik harbored alternative intentions. As soon as the divergence of opinions became evident, the sequence of events escalated dramatically. Ethiopia and Italy reached a formal agreement in the town of Wuchale in 1889, which they referred to as the Treaty of Wuchale (or ‘Uccialli’ in the Italian translation). The issue was that the Amharic (currently the official language of Ethiopia) and Italian versions of this agreement contained marginally different text. According to the Amharic version, the Emperor of Ethiopia might seek mediation from the Italian government during negotiations with other nations. However, the Italian version read “must” rather than “may.” Italy promptly communicated its recent acquisition to other European courts. However, Menelik did not become aware of the European interpretation of the treaty until Queen Victoria of England advised him that a copy of his letter would be sent to Rome.

Menelik was indignant. Concurrently, Italy was making preparations to strengthen its hold on Africa. The historical symbolism of Shewa, the “Trojan horse” of Italy, has been reassigned to the Tigray region situated in northern Ethiopia. However, Menelik swiftly and harshly reacted to these schemes. When Italy recognized that the Ethiopians would not retreat, it commenced preparations for an extensive military campaign.

Error committed by General Baratieri

Cities and fortifications in Ethiopia that were devoid of significant resistance from the local forces were captured by the Italians. To begin with, this was the Tigray region that consented to a treaty with Rome. Menelik, nevertheless, had already devised a retaliatory assault.

Prior to those occurrences, Ethiopia had been actively procuring European weaponry for a period of ten years. There were nearly 190,000 firearms imported into the nation between 1885 and 1895, including shotguns, rifles, and revolvers. In addition, 40,000 firearms were procured from Russia in 1895 with the assistance of the Kuban Cossack Army, led by Nikolai Leontiev, which dispatched a group of volunteer officers and medical personnel to Menelik’s aid.

Menelik assembled an army swiftly. The Italian commanders, on the other hand, paid little attention to the situation; they anticipated battling militias equipped with bows and spears.

As of September 1895, Menelik declared the commencement of hostilities. “Assist me, those of you who possess both determination and fervor; those who lack zeal—”May your prayers assist me,” he pleaded.

The Ethiopian military forces promptly launched an assault on the Italian garrisons. They assaulted the Amba Alagi garrison in December. In contrast to the 2,500-man Italian detachment, the 15,000-man Ethopians advanced and immediately vanquished the Italians. In exchange for its capitulation, the Mekelle garrison was permitted to retreat and retain its weaponry.

Under the leadership of General Oreste Baratieri, the 17,000-man Italian army engaged in combat with Menelik’s army. The Ethiopian forces, nevertheless, were numerous times more formidable. Rather than relying on information about Menelik’s army, Baratieri was duped into believing that the enemy was a pack of barbarians. Considering Menelik’s highly skilled intelligence service, the situation resembled a struggle between the visually impaired and the discerning, with the latter possessing formidable physical prowess.

Adwa

Baratieri executed resolute measures on February 25, 1896. The primary engagement between the two armies occurred in the city of Adwa on March 1.

Baratieri maintained a brigade column in reserve while advancing with three brigade columns. He intended to occupy the elevation in front of the Ethiopian army’s positions while marching at night. Had this strategy been executed, Menelik would have been placed in an exceptionally precarious predicament. Nevertheless, the march exhibited a lack of organization, as the columns proceeded haphazardly and rapidly lost communication with one another. Baratieri faced obstacles in every direction. Due to the limited combat capability of the Italian army, a significant number of personnel were punished by being deployed to African divisions. Indeed, the Italian army comprised a mere 11,000 men, with an additional 6,700 combatants having been enlisted in Africa. A minimal degree of discipline existed within the army. A similar assessment can be made of Menelik’s army; comprising more than 100,000 individuals, approximately 80,000 were armed.

Although Baratieri was unaware of it at the time, he had already been defeated in the war’s decisive engagement.

On March 1, at 3:30 a.m., an Italian brigade led by General Albertone arrived at the hill where they were intended to be stationed. However, upon reaching the hill, they quickly realized that their location was incorrect and that the actual position was further ahead. Instead of communicating his whereabouts to Baratieri, the brigade commander simply continued marching. At approximately 6:00 a.m., the brigade was attacked and forced back by the Ethiopians. Numerous Italian gunners perished on the spot despite their valiant efforts. The remaining forces were surrounded and compelled to surrender.

The principal forces of the Ethiopian army launched an assault against the central division of the Italian army. The remaining members of the Albertone brigade successfully advanced to the locations occupied by the Italian detachments, obstructing their artillery’s line of sight. Ethiopian forces pursued the Italians, quickly apprehended them, and launched an assault upon them.

The Ethiopian forces virtually engulfed the Italian brigades. Too late was the order to withdraw issued. At 12:30 p.m., the army was no longer under the direction of any individual. Although the remaining brigades exhibited a tenacious resistance, their eventual downfall was inevitable.

The surviving Italian forces escaped. One of the four brigade commanders was captured while the other two were slain. An estimated 8,000 soldiers perished or were captured, 1,500 were injured, and the army completely lost its ordnance and 11,000 rifles.

In addition, the Ethiopians lost numerous soldiers. The Italians, after all, attacked them with rapid-firing weapons. Some estimates put the number of Ethiopians injured at 10,000 and the death toll at 6,000; however, the veracity of these figures is questionable. However, in light of the Ethiopian army’s vast numerical advantage over the Italians, the Ethiopian side suffered relatively minor losses.

The outcomes of victory

Italy experienced a governance crisis upon learning of the defeat. Eritrea, which was under Italian control at the time along the coast of the Red Sea, was reached by the Italians as Ethiopian forces advanced northward and pushed them out.

His objective was not to entirely expel the Italians from Africa, as stated by Menelik. Menelik was concerned that a territorial claim over Eritrea would bolster the opposition forces within Ethiopia, given the notorious disloyalty of the Eritrean people.

Menelik, on the other hand, compelled Rome to sign a peace treaty in order to maximize the Emperor’s benefit from his victory. Ethiopia’s independence was unconditionally recognized and Italy committed to pay war reparations. The agreement, which was executed on October 6, 1896, was essentially an admission of defeat by Italy. Although it was acknowledged by all that this meant to be advantageous for Menelik, Italy managed to retain some territory in Africa.

During that period, Ethiopia successfully fought for and defended its independence, despite a turbulent successor history. Ethiopia fought alongside the Allies during World War II and went on to endure excruciating civil conflicts in the years that followed, but the 1896 victory would remain a resounding triumph in the country’s protracted quest for independence and unity.