In the 1950s and 1960s, David Robinson frequently accompanied his father, baseball legend Jackie Robinson, to New York’s Apollo Theater. David stated that his father would “shoot the breeze” with coworkers.

That was on 125th Street in Harlem, and the elder Robinson was not simply paying a visit. He ran a clothes business a block from the Apollo, so Black shoppers could avoid the hostility they frequently encountered when shopping in white-owned establishments. Jackie Robinson also co-founded Freedom National Bank, which is located directly across the street from the Apollo.

On this day 75 years ago, history books will forever recount how Jackie Robinson revolutionised the world by breaking the decades-old so-called gentlemen’s agreement that barred Black players from America’s game, Major League Baseball. Off the field, he was a notable business leader who promoted economic progress and entrepreneurship for African-Americans. Apart from the bank and apparel business, he co-founded the Jackie Robinson Construction Co., invested in apartment developments, and attempted to build a golf club despite being denied access to numerous courses due to his race, according to his son.

“As a people, we sought every opportunity — employment and business creation — to grow ourselves,” David Robinson told Forbes. “The same spirit that enables a man to steal home base 19 times is the same spirit that enables a man to win in business.”

Robinson’s pioneering leadership in business established precedents for African Americans and Black players such as Magic Johnson and LeBron James, who have parlayed their celebrity and multimillion-dollar paychecks into lucrative commercial endeavours.

Robinson, who died in 1972 at the age of 53, played for the Brooklyn Dodgers for ten seasons and was a member of the organization’s first world championship squad in 1955. He witnessed personally the societal injustices caused by racism, according to Della Britton, president and CEO of the Jackie Robinson Foundation, and thought that Black Americans should pursue economic empowerment, including entrepreneurship, in order to address those inequities.

“His legacy is that of not just advocating for economic empowerment and equal opportunity,” she said, “but actually demonstrating what that could look like.”

The National Urban League released a report this week highlighting how far Black Americans still have to go to achieve equality with white Americans. Their median household income, $43,862, is 37% less than white people’s median household income of $69,823. Additionally, black Americans are less likely to profit from property ownership, which is a major generator of generational wealth, and Census data reveal that black couples are more than twice as likely as white couples to be rejected a mortgage or home repair loan. Black households own only 13% of the wealth held by white households.

Jackie Robinson’s advocacy for Black entrepreneurship, as well as his personal entrepreneurial endeavours, began long before his playing career ended.

According to his foundation, he established the Jackie Robinson Garden Apartments in Brooklyn in 1951 and opened the Jackie Robinson Store in Harlem in 1952, which sold men’s clothes.

Robinson’s winning prowess and novelty in America’s favourite activity quickly elevated him to notoriety, and media groups quickly began granting him venues. In 1948, he created The Jackie Robinson Radio Show through a deal with New York’s WMCA. He signed a partnership with WNBC in 1952 to oversee community affairs and began writing a nationally syndicated column for the New York Post in 1959.

“He recognised his celebrity status as an athlete and exploited it to his benefit — and to the favour of Black people,” Britton explained. Robinson used those forums, she continued, to “freely express his views” on reducing barriers to economic opportunity.

Robinson made the equivalent of $2.8 million in 2022 dollars throughout his playing career from 1947 to 1956, according to his foundation, which placed him among the game’s top earners in an era before collective bargaining and mega-television-rights deals.

Robinson received no offers to coach or work in baseball following his retirement, according to his foundation. He was, nevertheless, offered a position as vice president of personnel by coffee firm Chock Full o’Nuts in 1957. That is how he became the first African-American senior leader in a large American corporation with a majority-Black staff.

In 1964, he left Chock Full o’Nuts and co-founded Harlem’s Freedom National Bank. Robinson chaired the bank, while co-founder William Hudgins served as president. It was founded to promote access to funding for African-American communities and grew to become the state’s second largest majority-Black-owned bank, trailing only Carver Federal Savings Bank.

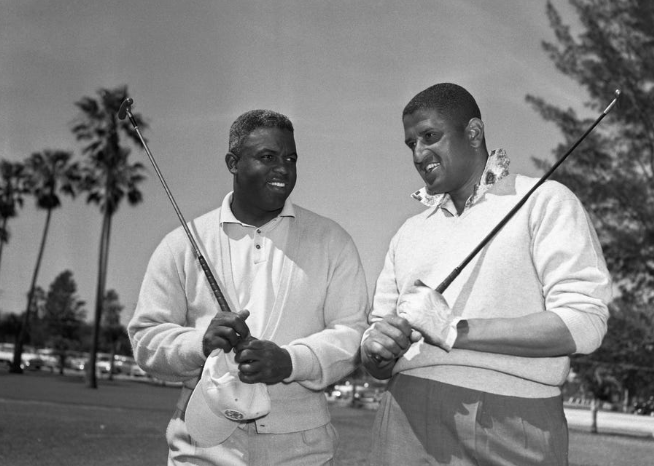

Along with funding, Robinson promoted housing as a critical component of Black economic growth. In 1963, he joined with heavyweight boxing champion Floyd Patterson on a real estate development project in Wurtsboro, New York. Robinson founded the building company in 1970 with the express purpose of constructing low-income houses.

David Robinson expressed pride in the Jackie Robinson Foundation, which his mother Rachel Robinson founded in 1972. The Jackie Robinson Foundation has developed over 1,800 young leaders. The charity plans to dedicate a museum to the baseball legend in July. David Robinson founded Sweet Unity Plantations Coffee in Tanzania, a cooperative of over 200 small family-owned coffee farms.

“In his continued pursuit of social improvement for the African-American community and for the United States as a whole,” David Robinson remarked. “There is really no distinction between his baseball goals and his life goals in politics and business.”

Robinson was also active in community activism and politics. Several of his political choices eclipsed some of his remarks about economic development. He backed Republican Richard Nixon over Democratic John F. Kennedy in the 1960 United States presidential election, a decision that irked many Black voters, according to Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro League Baseball Museum in Kansas City.

“I remind folks that during that age, every black person’s home was required to have three photographs on the wall – one of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., one of John F. Kennedy, and one of Jesus,” Kendrick added.

While Robinson later expressed sorrow for some of his political choices, Kendrick maintained that he was always his own man. And he was adamant in his opinion that “economic empowerment was the way to social change.”