On June 6, 1944, my grandpa Charles “Charlie” Truman arrived in Normandy with 150,000 other Allied troops to free France and the rest of Western Europe from the Nazis. He didn’t think he would ever see his pregnant wife again.

However, a choice he made the night before saved his life.

He was one of the first 150,000 Allied troops to land on Sword Beach for Operation Overlord, the famous attack of northern France that ended the Second World War. He was 26 years old at the time.

As troops got into the landing boats the night before the attack, they were told to leave their bags behind.

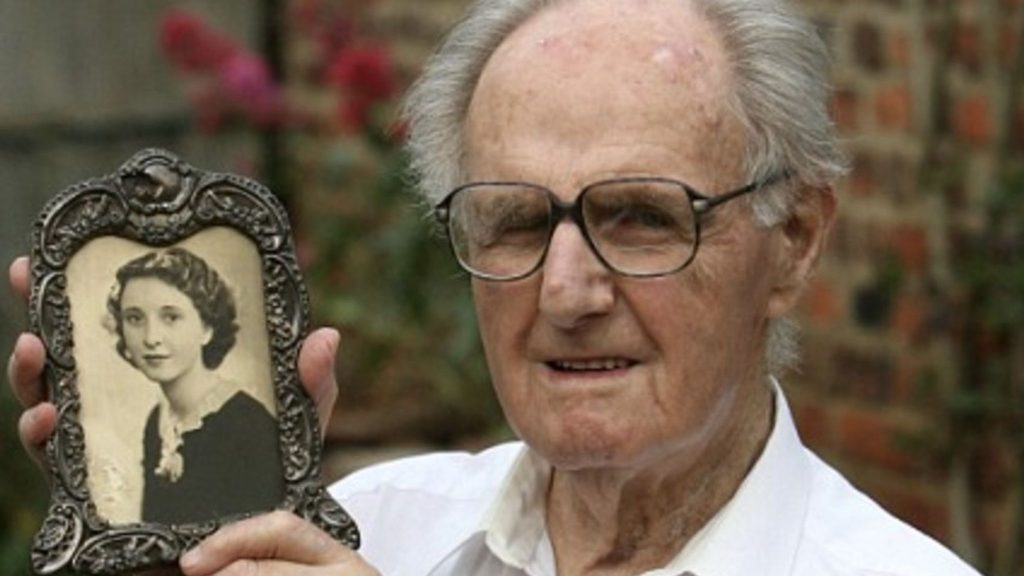

My grandfather, or “grandpop,” never really disobeyed, but when he thought about how scary it would be to not know what would happen to him, he chose to keep one thing: a silver frame with a picture of his wife Joyce.

She was five months along with giving birth to their first child, my aunt.

A few hours after making that hasty choice, at dawn, he was running hard and fast, moving inland after arriving on the beach in Normandy.

Their goal was a German bunker complex with the code name Hillman.

He ran ahead of his group without realizing how big the Hillman fortress was in front of him. An overhead shot sent by intelligence just days before D-Day showed the fortification covered in plants, making it impossible to see how big it really was.

Sixty German forces were in the network of bunkers below ground.

Charlie and his friends from A Company were moving forward with fixed bayonets when they were hit by heavy machine gun fire.

When German soldiers saw Charlie, they opened fire and shot him down.

Charles was knocked down when a bullet hit him in the lungs. Right away, a second round came in, this time directed at his chest.

The second bullet went through my grandfather’s arm and hit the metal picture frame that became his personal body armor.

He fixed himself up with the only bandage he had and began to crawl back down to the beach.

His blood loss was too high, so he had to stop. Troops found him and brought him back to where he was waiting for the medic boats, while gunfire fell all around the injured on the shore.

Charlie made it back to England, but not many of his friends did that day. He was in chest units all over the country for 16 weeks.

A short message was sent to my pregnant grandmother to let her know that her husband was seriously hurt.

No one told her how sick he was when she went to the south coast by herself to find him.

It had been bad; at one point, he was taken off of CPR and his last rites were said, but he lived.

Like a lot of other soldiers who lived through D-Day, my grandpa didn’t tell the stories very often.

He was upset about it for years, I know. But when it did happen, he always said that luck and love had come together to save him.

It’s hard to pick out the most interesting survival stories from D-Day heroes, especially if the event is part of your family’s past.

This is where my grandpa, Charles “Charlie” Truman, was born and raised. As early as age seven, he started working by delivering meat for his family’s butcher shop. While doing this, he learned how to do the job.

Before the war in 1939, he quit school when he was 14 and worked as a butcher full-time.

He joined the Suffolk Regiment, which is now called the Royal Anglian Regiment, that same year and became the runner for his company.

People who worked as runners were supposed to do their jobs quickly. Charlie had always been very good at cross-country, so this job came naturally to him.

As a child, he would let me touch the bullet holes because he didn’t want to think about how scared and horrified he must have been that day.

He lost a lot of friends and came so close to dying that an act of love was the only thing that saved him.

It was December 2011 when Charlie Truman died.